Blog

Gender inequality and invisible work in the platform economy

Date Posted: Monday 7th February 2022

Written by Dr Deborah Giustini

On-demand platform work is often about matching customers who want invisible work done with those who will do it.

In the past few years, the selling and buying of physical and digital services through online platforms has gained attention across policy and research debates on the future of work. Around 11% of the EU’s workforce—24 million people—is estimated to provide services through digital platforms as a primary or secondary income source. Commonplace arguments indicate the urgent need for rethinking platform workers’ uncertain employment status. In 2020, it was estimated that 42% of women are part of this workforce in Europe. However, their experiences remain vastly unseen.

One point is of specific concern: the platform economy thrives on gender asymmetries that trap women into invisible labour.

Women’s invisible work in the platform economy

Platform work is increasingly associated with ‘invisible work’, which rests both on backstage activities performed as a precondition for customer experience or organizational expectations, and their cultural, legal, and spatial devaluation which prevent society from ‘seeing’ work done. Research suggests that platform workers are made invisible due to being an interchangeable, faceless online crowd; because of the borderless nature of online activities; and because platforms’ algorithmic management automates work allocation, regardless of workers’ discretion and skill use. Finally, this invisibility is compounded by the lack of regulation of platform workers’ employment status globally. This impedes association opportunities, while fear of retaliation makes workers’ exploitation less visible than in traditional settings.

Occupational segregation

Feminist sociologists uncovered aspects of female work that consistently remain invisible. Initially theorised as women’s unpaid work in the private sphere (e.g. housework), they extended invisible work to paid, formal employment by addressing occupational segregation, or the distribution of workers based upon demographic characteristics as gender. It is a well-established fact that women are channelled into lower-status, less visibly-prestigious positions which privilege gendered assumptions – for instance ‘nurturing’ jobs as nursing, teaching, and care work.

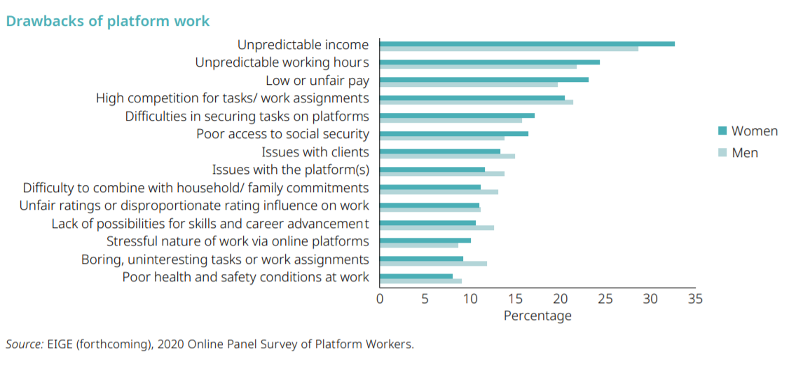

Occupational segregation in the platform economy is equally well-established. Whereas men occupy the most technical roles as IT or R&D, women are mostly found in cleaning, caring, tutoring, writing and translating jobs. The reasons for this ‘digital’ occupational segregation are varied – from customers’ choice of men for more specialized tasks, to women’s limited availability due to housework, as well as biases in algorithmic management for work allocation. The activities of gig work are thus predicated on conventional lines of occupational segregation which pushes women to less prominent jobs in societal perception.

Flexibility

Platform work is also gendered across ‘flexibility’ lines, which is usually seen as a significant benefit to women more than men. Women, in fact, often need flexibility to shoulder caregiving and housework demands whilst securing income. Extended through the reach of ‘digital capitalism’, flexibility explains part of women’s motivation to engage with platform tasks to gain autonomy and control over the pace and content of work, in contrast with less agile, traditional workplaces. Nonetheless, the irregularity and instability of digital work pushes both men and women to operate on multiple platforms, or for longer hours to get sufficient work. As tasks are not easily available, many spend time searching for these and dealing with requestors. These activities devaluate workers’ time and make their efforts invisible, since they are framed as ‘not real’ and unpaid work.

However, it is women who bear the brunt. Largely due to social norms, household responsibilities, and lack of care infrastructure, on average women perform fewer hours of paid digital work, though the number of hours spent on unpaid tasks is similar to men’s. Therefore, flexibility is conditional upon whether women have access to platform work in the time frame they can dedicate to paid activities – a routine revealing the invisible boundaries between the ‘public’ and the private spheres for many women.

Although additional flexibility mechanisms of the platform economy, such as the ‘independent contractor’ status operate across men and women’s positions, its invisibilising effects are also stronger on women. Platform work is not accompanied by labour rights such as sick pay, meaning that women are not entitled to statutory rights as paid maternity leave. Such aspects raise questions about women’s invisibilised status as both their work and their private life events are excluded from the legal protection of ‘employment’ of platform activities.

Seeing work that is done

Women’s work in the platform economy is prevalently gendered and located at the interstices of an already invisible workforce. Understanding how the platform economy appropriates and tacitly replicates normative employment is key to deconstruct its tropes as empowering women with greater autonomy, earnings opportunities, and decision-making. We must confront that the platform economy thrives on women’s employment vulnerabilities and its invisibility, as it largely relies on structures which emphasise their role as doubly marginalised – online and offline. Given the dominance of gender-blind discussions of platform work, it is not surprising that inequality remains its part and parcel.

Finally, the role of platform economy in women’s employment has been growing significantly under the Covid-19 pandemic, as women are overrepresented in the hard-hit service and hospitality industries, and because they are likelier than men to leave jobs for childcare. If we are to rethink a post-pandemic economy that works regardless of gender, we need to start looking at the unbalanced employment reality of platform economy.

Dr Deborah Giustini is a Postdoctoral Fellow at KU Leuven (Belgium), where she investigates the employment experiences and invisible labour of freelance, platform workers in Europe and Japan. @DeborahGiustini