Blog

Gender Segregation by Field of Study in Higher Education: A New Way of Gender Inequality?

Date Posted: Friday 14th December 2018

The first blog post of our ECN series "Women and the Economy"

Izaskun Zuazu, a PhD candidate at the Department of Applied Economics in the University of the Basque Country (UPV/EHU), writes about how gender segregation in university subjects has an impact on the gender pay gap.

Like in many other Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries, women in the UK outnumber men in the body of graduates from higher education (HE). Based on OECD data, women made up to 57% of HE graduates in 2012. However, women concentrate in humanistic and health related fields whereas men concentrate in technical and scientific-related fields. This phenomenon, known as horizontal gender segregation in HE, is considered an issue of first-order importance insofar as it shapes the skill composition of the future workforce and thus may represent a hurdle for labour market productivity gains and economic development. Furthermore, empirical research found that gender segregation in education accounts for a notable share of the gender pay gap. As suggested in a recent article, it seems that HE qualifications earned by women are not enough to close the pay gap, as qualified women earn little more than many men of the same age without degrees. Thus, the field of education chosen by women, which differs from that of men, could be behind the pay gap.

As of the causes of gender segregation in HE, social scientists from different disciplines tend to debunk the oft-repeated arguments of gender differences in cognitive skills. To the contrary, empirical evidence provides leverage to socio-economic factors, such as gender differentials in career and family aspirations, gender-based discrimination, and cultural values as major causes of horizontal gender segregation in education (see Ceci et al., (2014) or Bertrand (2017)). This blog post offers a comparison between horizontal gender segregation in HE in the UK and other OECD countries using a database I constructed for one of my PhD dissertation chapters.

Horizontal Gender Segregation in HE: the case of UK and other Western countries

The dissimilarity index (Duncan and Duncan 1955) measures gender segregation at national levels and it is commonly used both by scholars and policy-makers working on gender segregation. The index provides the percentage of women – or men, depending on the perspective from which it is computed – who should trade fields to reach the same distribution across fields within HE as that of men.

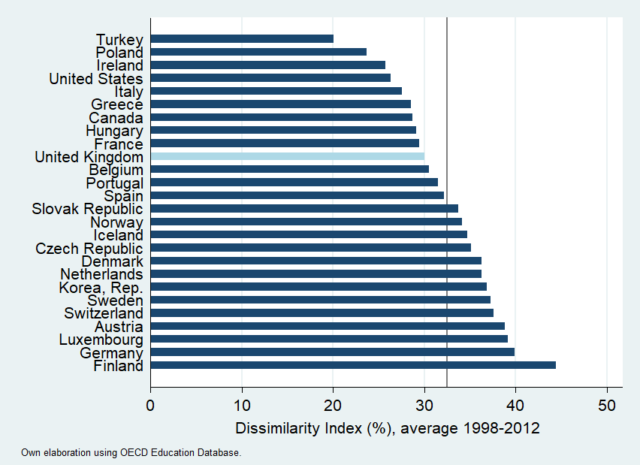

Using administrative information taken from the OECD Education Database, the graph below shows the average dissimilarity index during 1998-2012 for the UK as well as for the 26 OECD countries in my study. On average, 30% of women graduates in UK should change field of study so as to have the same distribution by field of study as men, which is slightly lower than the sample average (32%, vertical line in the graph). The least segregated country is Turkey (20%) and the most segregated one is Finland, where more than 44% of women should change field so as to bring the same distribution as men.

A striking pattern shown by this graph is that more affluent and gender-egalitarian countries have also higher levels of gender segregation in HE, a feature that goes precisely in line with Education-Gender-Equality paradox as also found in social psychology. Indeed, the higher levels of horizontal gender segregation in more gender-egalitarian countries is also a recurrent finding in economic research, as it is generally found that more gender egalitarian ideals might favour the divergence of preferences of women and men, as recently found here.

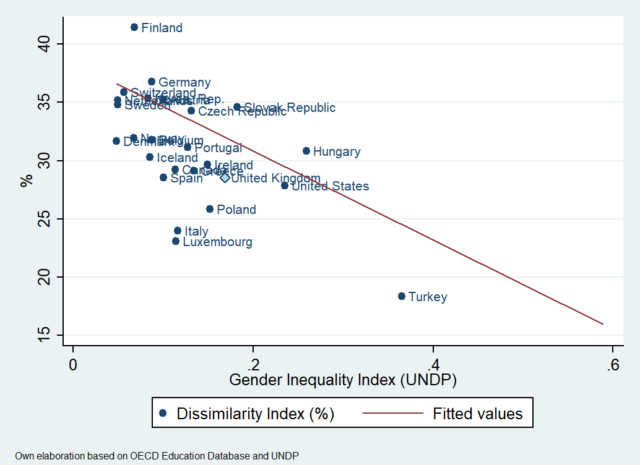

To delve deeper in the relationship between gender inequality and gender segregation in HE, the following graph shows the levels of gender inequality, using the Gender Inequality Index provided by the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) – which measures gender inequalities in health, empowerment and economic status – and horizontal gender segregation in HE, using the dissimilarity index shown above. The following graph shows how counties with low levels of gender inequality (Denmark, Finland, Sweden and Norway) are also the more segregated in HE.

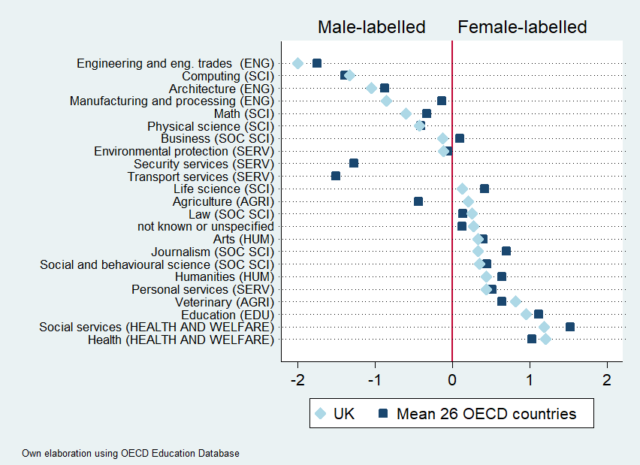

I next turn the attention towards how each field of HE is segregated. This is done by using the association index of Charles and Grusky (1995) which provides the factor at which each field of study is labelled as male (negative values), is a gender-neutral field (values close to zero), and as female (positive values). The beauty of this measure is that it allows us to compare the extent to which each field is segregated by looking at the absolute values of the index. The association index shows also high heterogeneity of gender-labelling within STEM fields. Although STEM fields are generally male-dominated, Life Science is a female-dominated field. Similarly, Agriculture, which is a male-dominated field, is composed by the subfields of Agriculture, Fishery and Forestry (male-labelled) and Veterinary (female-labelled).

(Note Graph 3: Transports and Security services are included in other SERVICE in the UK as stated in the OECD Database in Education “Education at a glance https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?datasetcode=EAG_GRAD_ENTR_RATES. ENG (Engineering); SCI (Science); SOC SCI (Social Science); SERV (Services); AGRI (Agriculture); HUM (Humanities and Arts); EDU (Education). Corresponds to the ISCED1997 Classification, used by OECD Education at Glance.)

The figure above shows the extent to which each subfield of HE is gender-labelled as male, neutral or female in the UK, and compares it with the average for other OECD countries. The most segregated field in the UK is Engineering and Engineering Trades, which happens to be male-dominated, and it is slightly more male-labelled than the sample average. Among the male-dominated fields, UK shows generally higher levels of gender segregation than the sample average, with the exception of Computing. For relatively gender-neutral fields (close to the red vertical line), the trends in UK higher education system differ from the rest of the 26 OECD countries in the sample: Business is male-dominated in the UK whereas the field is on average female-dominated for the rest of the sample. Another special feature of the UK is that Agriculture is dominated by women, whereas it is usually male-labelled field in OECD countries. As regards female-labelled fields, the UK shows lower levels of gender segregation than the sample average. The most female-labelled field is Health, whereas in the sample of OECD countries the most feminized subfield is Social Services. Journalism is slightly less feminized in the UK than in the rest of the sample of countries.

A new form of gender inequality?

The observation of higher levels of horizontal gender segregation in HE in more affluent countries, such as the Scandinavian countries, is particularly puzzling against the backdrop of affirmative action, anti-discrimination policies, and gender-egalitarian ideals in Western countries. One potential explanation behind this puzzling observation is that women in countries with more gender inequality seek economic freedom by pursuing STEM fields because they are precisely conducive to higher-paid jobs in the labour market. This argument is also formulated as the indulging-our-gendered-selves account provided in Charles and Bradley (2009), suggesting also that weakening material constraints may favour the segregation of women in fields of education conducive to lower-paid jobs in affluent countries.

Finally, and as suggested by Diane Elson, “[o]ld forms of gender inequality are weakened but new forms of gender inequality emerge”. Therefore, a pending quest is whether horizontal gender segregation in HE can be a new form of gender inequality in Western societies, and whether we will see increasing horizontal gender segregation in HE as Western societies erode other gender inequalities in coming cohorts of graduates.